Bicycle Uprisings Past and Present

On July 22, 1987, Mayor Koch stood on the steps of City Hall flanked by his police and transportation commissioners and declared that bicycling would be banned on Fifth, Park, and Madison from 31st to 59th Streets, Monday-Friday, 10am-4pm, starting in September. The ban was a clear attack on bike messengers, who were being scapegoated in the press for the dangerous and congested streets of NYC. Any unbiased observer could see (and still can) that the actual cause of danger and congestion in our city’s streets was automobiles. Fortunately, this unfair treatment of one subgroup of cyclist struck a nerve among many others – from activists to commuters to recreational riders – and brought together the cycling community in a spirit of direct action that helped usher in an era of victories for a livable city.

On July 22, 1987, Mayor Koch stood on the steps of City Hall flanked by his police and transportation commissioners and declared that bicycling would be banned on Fifth, Park, and Madison from 31st to 59th Streets, Monday-Friday, 10am-4pm, starting in September. The ban was a clear attack on bike messengers, who were being scapegoated in the press for the dangerous and congested streets of NYC. Any unbiased observer could see (and still can) that the actual cause of danger and congestion in our city’s streets was automobiles. Fortunately, this unfair treatment of one subgroup of cyclist struck a nerve among many others – from activists to commuters to recreational riders – and brought together the cycling community in a spirit of direct action that helped usher in an era of victories for a livable city.

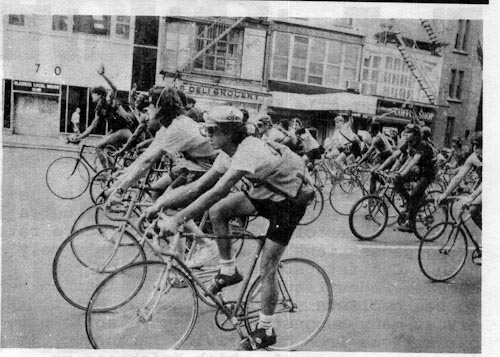

That spirit of direct action rose, as it always does, from the streets. Steve Athineos, a three-year veteran of bicycle messengering in NYC at the time, recently told me his version of what happened 25 years ago. One day in July he was cycling up Park Avenue, delivering a package, when a car sped past him and turned right into his bicycle and his body – an image all too familiar to any of us who regularly ride in New York City. He sat on the sidewalk bruised and bleeding as the police came, checked to make sure the driver wasn’t too shaken up, then left without asking him any questions about the event or his injuries – another all-too-familiar experience for New York City cyclists. He rode down to the park on the SE corner of Houston and 6th Avenue,  where messengers met daily to decompress and share stories. When Steve complained about the reckless driver and negligent police, several other messengers told similar tales, and their mutual discontent inspired them to rise up and take the streets. Six of them rode side-by-side up Sixth Avenue and forced traffic to slow down behind them all the way to Central Park.

where messengers met daily to decompress and share stories. When Steve complained about the reckless driver and negligent police, several other messengers told similar tales, and their mutual discontent inspired them to rise up and take the streets. Six of them rode side-by-side up Sixth Avenue and forced traffic to slow down behind them all the way to Central Park.

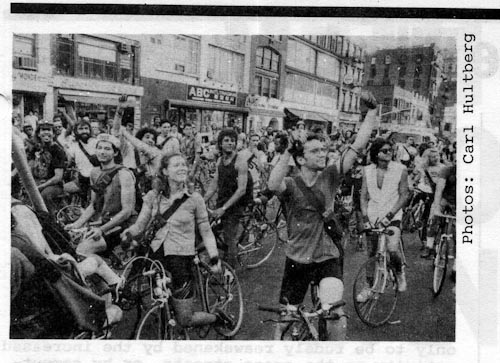

The next day, when the messengers reconvened at the park after work, a reporter from the New York Times was there to interview them. The reporter asked about their direct action from the night before and inquired if it was organized to protest the proposed Midtown bike ban. Athineos told the reporter that it wasn’t organized, much less to protest anything, and that none of them  had even heard of the bike ban. He went on to deliver a few sound bites speaking truth to power, and the reporter raced off to the write the story. The next day, when the messengers rode up to their normal meeting place after work, Sixth Avenue was flanked with news trucks.

had even heard of the bike ban. He went on to deliver a few sound bites speaking truth to power, and the reporter raced off to the write the story. The next day, when the messengers rode up to their normal meeting place after work, Sixth Avenue was flanked with news trucks.

While the energy of the bike messengers was palpable, disorganized outbursts of frustration rarely lead to tangible change. The group that brought organization to this movement was Transportation Alternatives (TA), NYC’s bicycle advocacy group. Shortly before the Midtown bike ban was announced, TA had changed its leadership in preparation to fight just  such a ban. The new Board of Directors had little time to prepare for this fight, but after seeing press from that day, they quickly tapped into the energy of the messengers. They used their membership base to encourage other types of cyclists to join the movement, worked their modest political connections, and began challenging the mayor’s edict in court.

such a ban. The new Board of Directors had little time to prepare for this fight, but after seeing press from that day, they quickly tapped into the energy of the messengers. They used their membership base to encourage other types of cyclists to join the movement, worked their modest political connections, and began challenging the mayor’s edict in court.

The last element of the make-shift coalition to fight the ban was delivered by Steve Stollman, who offered the movement his connections with pamphleteers and European cycling advocates, and more importantly his East Houston Street storefront, where the cyclists held meetings, painted banners, and printed flyers. These three formerly-disconnected forces worked in concert and created a series of direct actions that would  change New York City forever.

change New York City forever.

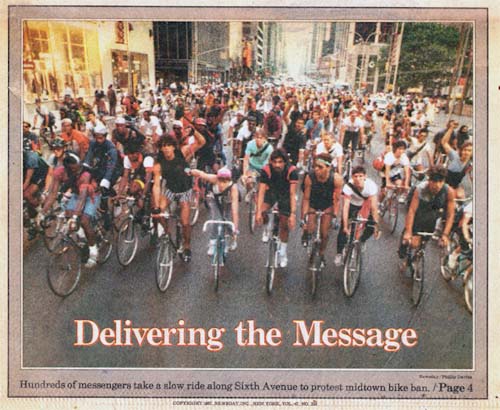

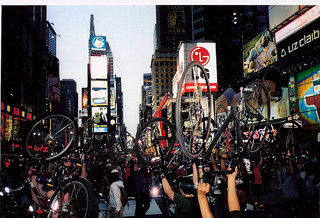

According to Charlie Komanoff, the new head of TA at that time, twice a week for the next month, at around 5:30pm, “Masses of cyclists, sometimes half a thousand and occasionally more, spread across Sixth Avenue and paraded the three miles from Houston Street to Central Park South. Our stately pace, perhaps 5mph, was slow enough that passersby could look past our bikes and see our bodies and faces. Walkers and joggers could join our ranks. We were slow enough that we could and did stop at red lights. Letting foot and auto traffic cross at the green was a stroke of genius. It certified cycling as city-friendly.” Their banners not only decried Koch and the Bike Ban, but promoted positive messages such as safer streets and cleaner air. This and the image of gritty messengers alongside middle-class commuters and activists, garnered positive press coverage almost every day.

I n late August, five weeks after Koch’s City Hall announcement, the bike ban was overturned in the courts on a technicality: the City’s failure to publish official notice. But the fact that the City declined to then publish notice and enact the ban in the fall is testament that the cycling community won the battle in the streets, forged a powerful cycle advocacy community, and perhaps won the hearts and minds of many New Yorkers. The slew of victories for livable streets and green infrastructure in the next five years surely point to this conclusion.

n late August, five weeks after Koch’s City Hall announcement, the bike ban was overturned in the courts on a technicality: the City’s failure to publish official notice. But the fact that the City declined to then publish notice and enact the ban in the fall is testament that the cycling community won the battle in the streets, forged a powerful cycle advocacy community, and perhaps won the hearts and minds of many New Yorkers. The slew of victories for livable streets and green infrastructure in the next five years surely point to this conclusion.

Largely led by TA, the cycling community won important victories with direct action in the late eighties and early nineties: full-time access to River Road in New Jersey; legal access to the south path of the George Washington Bridge; a shift in public opinion that clean air should be a priority in NYC transportation planning; and re-establishment of the permanent bike lane over the Queensboro Bridge, which had been opened to automobiles during weekday afternoons and evenings. In an unprecedented victory for direct action, when six activists arrested for disorderly conduct while riding their bikes in the action over the Queensboro Bridge had their day in court, the judge declared that their protest had served the public interest by protecting cyclists and pedestrians who might

Largely led by TA, the cycling community won important victories with direct action in the late eighties and early nineties: full-time access to River Road in New Jersey; legal access to the south path of the George Washington Bridge; a shift in public opinion that clean air should be a priority in NYC transportation planning; and re-establishment of the permanent bike lane over the Queensboro Bridge, which had been opened to automobiles during weekday afternoons and evenings. In an unprecedented victory for direct action, when six activists arrested for disorderly conduct while riding their bikes in the action over the Queensboro Bridge had their day in court, the judge declared that their protest had served the public interest by protecting cyclists and pedestrians who might  have ventured onto the bike path during hours when it was open to automobiles!

have ventured onto the bike path during hours when it was open to automobiles!

For 25 years since the Bicycle Uprising, direct action has continued to make NYC’s streets safer, greener, and more livable. In recent years, TA has changed its focus to advocacy while Time’s Up! has carried on the torch of direct action. Together they have helped bring about radical change in NYC: hundreds of new bike lanes, thousands of new cyclists, and a political climate where people cannot believe a ban on biking was ever even proposed.

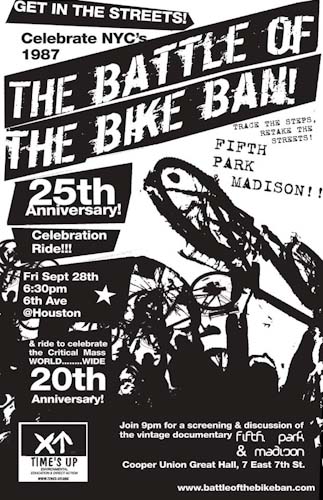

But there is much more work to be done. Hundreds of pedestrians and cyclists are still killed by automobiles every year and the NYPD does little to  investigate these deaths let alone prosecute the traffic infractions that lead to them. For all these reasons, we are organizing a celebration and direct action for the 25th Anniversary of the Bicycle Uprising and the 20th Anniversary of Critical Mass – a ride that rose out of the spirit of the bike ban protests and continues across the world on the last Friday of every month.

investigate these deaths let alone prosecute the traffic infractions that lead to them. For all these reasons, we are organizing a celebration and direct action for the 25th Anniversary of the Bicycle Uprising and the 20th Anniversary of Critical Mass – a ride that rose out of the spirit of the bike ban protests and continues across the world on the last Friday of every month.

On September 28, 2012, we will meet in the park at Houston and 6th Avenue at 6:30pm and bike the ride that defeated the bike ban – 3 miles up 6th Avenue to Central Park – in solidarity with Critical Mass. We’ll ride back down Park Avenue to the Great Hall at Cooper Union, where we will show the original movie made about the uprising – Fifth, Park and Madison.

Please join us for the ride, and donate and sign-up to volunteer now to make this event a success!

-Keegan, Time’s Up!

CLICK HERE for contact info or more information on 25th Anniversary of the The Battle of Bike Ban